laboratoire écologie et art pour une société en transition

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Created by tree-artists Thierry Boutonnier and Eva Habasque, and designed with least, CROSS FRUIT (formerly “Verger de Rue”) is a co-creative urban ecology and arboriculture art project. The project enables Onex residents of all ages, with the help of professionals, to participate in the design, creation, and maintenance of an orchard based on their desires and the specific characteristics of their neighbourhood.

CROSS FRUIT is a play on words between crossfit, the high intensity fitness regimen, and nature’s sweet treasures. Over the course of this long-term project, various events will mark the orchard’s seasons. From 2024 to 2026, participants will be encouraged to exchange know-how, experiences, and methodologies through co-creative workshops, paving the way for a form of solidarity-based eco-design.

As well as being a place of food sovereignty, the orchard will be home to a sculpture garden featuring sporty, playful, and inclusive installations. These structures, such as the “watering bike”, will serve to help trees grow and meet their needs, and will showcase the robustness and resilience of the plant world.

What we’ve done

The first phase of the project was devoted to in situ research in the Onex region, while involving local residents in a community-based eco-design project. Brisolée (a traditional meal based on fire-roasted chestnuts), seed collection, and the creation of shoots ran through the autumn and winter of 2023. In the spring of 2024, during our Olympic/”Crossfruit” Games, the shoots were playfully transported to the future orchard. Over the summer, we organized various activities to support the growth of the plants and celebrate this new collective space, notably during the first Festin Fruité (Fruity Feast). In 2025, we planted a selection of fruit trees developed in collaboration with the local community. The trees were collectively adopted, strengthening the bond between the residents and the orchard. The first workshops to support the involvement of tree caretakers began following the planting.

What we’re doing

We are currently co-creating a sculpture garden that meets the needs of fruit trees. Sturdy tree structures, a shed, and stakes support the trees’ growth. Tree-care and art workshops continue to be offered regularly to a wide audience. We also welcome sheep twice a year to graze in the orchard and contribute to the ecological management of the site. At the same time, young filmmaker Simon David is working on a series of videos about the Onex community and its relationship with the land.

What’s next

As the seasons change, new activities will enrich the orchard and strengthen its collective ownership. In fall 2025, playful and interactive sculptures will be created, inviting young and old alike to collectively build and explore this living space, and the second Festin Fruité (Fruity Fest) will bring the community together. Winter will welcome the screening of the first episodes of Simon David’s video series, while regular workshops will involve the tree sponsors in the life of the site.

Sign up to the newsletter to keep up-to-date and get involved!

newsletter

All participatory actions and locations will be communicated on our website and via least’s newsletter.

transdisciplinary team

Thierry Boutonnier – arborist artist

Eva Habasque – arborist artist

Gabrielle Rossier – artist-in-residence at least

Simon David – director

Tiago Veloso – sports trainer

Irina Georgieff – movement expert

Gabriela Pollonini – occupational therapist

Xavier Lacroix – physiotherapist

Karine Gondret – pedologist

least would like to thank all the people that contributed to the project by sharing their time, knowledge and resources:

Atelier Richard; Ateliers ABX (Astural); Association des Habitants d’Onex-Cité (AHOC); BUPP Onex; Fondation des Evaux; Jardin robinson Onex; MACO; Matières Naturelles; Pépinière Europlant; Pot’âgés; Pro Specie Rara; Sablière du Cannelet SA; Villa Yoyo d’Onex; Ville d’Onex; Association pour une Alimentation Durable à Onex (AADO); Servette Rugby Club

media

The Nest

Reading

A poetic reflection by Gaston Bachelard on the nest as a symbol of intimacy, refuge, and imagined worlds.

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Faire commun

Se rencontrer sur le seuil

Everything Flows

Reading

Life relies on a delicate synchronization between the rhythms of living beings and the cycles of the Earth.

Faire commun

Vivre le Rhône

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Living Soil

Reading

Although we walk on it every day, we rarely consider the importance of soil in our lives.

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Faire commun

Arpentage

Autumn in the Garden

Reading

“We say that spring is the time for germination; really the time for germination is autumn”.

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Faire commun

Arpentage

Ô noble Green

Reading

The «Ignota Lingua» by Hildegarde of Bingen.

CROSS FRUIT

Common Dreams

Faire commun

The Multiciplity of the Commons

Reading

Yves Citton discusses commons, negative commons, and sub-commons with us.

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School

Faire commun

Arpentage

CROSS FRUIT

Experiencing the Landscape

Reading

The complexity of the term ‘landscape’ can best be understood through the concept of ‘experience’.

Vivre le Rhône

Faire commun

Arpentage

CROSS FRUIT

Se rencontrer sur le seuil

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Video

An urban ecology project that involves citizens in the design, creation and maintenance of an orchard.

CROSS FRUIT

The Gesamthof recipe: A Lesbian Garden

Reading

The Gesamthof is a non-human-centred garden, a garden without the idea of an end result.

CROSS FRUIT

Peau Pierre

Wild Bread

Reading

An essay about the experience of hunger in Europe in the modern age.

Faire commun

CROSS FRUIT

A Sub-Optimal World

Reading

An interview with Olivier Hamant, author of the book “La troisième voie du vivant”.

Common Dreams

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Learning from mould

Reading

Even the simplest organism can suggest new ways of thinking, acting and collaborating

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

The Nest

Here is an excerpt from The Poetics of Space by 20th-century French philosopher Gaston Bachelard. In this work, Bachelard explores spaces of human intimacy – houses, drawers, nooks, nests – not as physical objects, but as places imbued with life and imagination. The passage featured is a poetic and thoughtful meditation on the nest, viewed as a vital refuge, the centre of a universe that is both real and imagined.

It is the living nest, however, that might introduce a phenomenology of the real nest, the nest found in nature, which becomes, for a fleeting moment (and the word is not too grand), the centre of a universe, the marker of a cosmic situation. I gently lift a branch, the bird is there, brooding on its eggs. It does not fly away. It only trembles, slightly. I tremble at making it tremble. I fear that the nesting bird knows I am a man, that being who has lost the trust of birds. I remain still. Slowly – so I imagine – the bird’s fear and my fear of causing fear subside. I breathe more easily. I let the branch fall back. I’ll return tomorrow. But today, I carry a quiet joy: the birds have built a nest in my garden.

And the next day, when I return, walking even more softly, I see, at the bottom of the nest, eight eggs of a pale pinkish white. My God! How small they are! How tiny a hedge bird’s egg is!

There is the living nest, the inhabited nest. The nest is the bird’s home. I’ve long known this, it’s long been said to me. It’s such an old truth that I hesitate to repeat it, even to myself. And yet I have just relived it. I recall, with a clear and simple memory, those rare moments in life when I have discovered a living nest. How few and precious are such true memories in a lifetime!

I now fully understand Toussenel’s words:

“The memory of the first bird’s nest I found on my own has remained more deeply etched in my mind than that of the first Latin prize I won at school. It was a lovely greenfinch’s nest with four grey-pink eggs, traced with red lines like a symbolic map. I was struck on the spot by an unspeakable joy that rooted me there for over an hour. It was my calling that chance revealed to me that day.”

What a beautiful passage for those of us seeking the sources of our earliest fascinations! When we resonate, even from afar, with such a shock, we better understand how Toussenel could integrate, in both life and work, the harmonic philosophy of Fourier, adding to the bird’s life an emblematic dimension, a universe of meaning.

And even in ordinary life, for someone who lives among woods and fields, the discovery of a nest is always a fresh emotion. Fernand Lequenne, the plant lover, walking with his wife Mathilde, spots a warbler’s nest in a blackthorn bush:

“Mathilde kneels down, reaches out a finger, brushes the fine moss, holds her hand there, suspended…

Suddenly, I shudder.

I’ve just discovered the feminine meaning of the nest, perched in the fork of two branches. The bush takes on such human significance that I cry:

– Don’t touch it, whatever you do, don’t touch it!”

Drawing: Anaëlle Clot.

Toussenel’s shock, Lequenne’s shudder, both carry the unmistakable mark of sincerity. We echo them in our reading, since it is often in books that we experience the thrill of “discovering a nest.” Let us then continue our search for nests in literature.

Here is an example where a writer intensifies the nest’s role as home. We have borrowed it from Henry David Thoreau. In his writing, the entire tree becomes, for the bird, the vestibule of its nest. Already, the tree that shelters a nest partakes in the mystery of the nest. For the bird, the tree is a refuge.

Thoreau shows us the woodpecker making a home of the whole tree. He compares this act of possession to the joyful return of a family moving back into a long-abandoned house: “Just as when a neighbouring family, after a long absence, returns to their empty home, I hear the joyful sounds of voices, the laughter of children, and see smoke rising from the kitchen. The doors are flung wide open. The children race through the hall, shouting. So too, the woodpecker darts through the maze of branches, drills a window here, bursts out chattering, dives elsewhere, ventilates the home. It calls out from top to bottom, prepares its dwelling… and claims it.”

Thoreau gives us, all at once, the nest and the house unfolding. Isn’t it striking how his text breathes in both directions of the metaphor: the joyful house becomes a vibrant nest – and the woodpecker’s trust, hidden in its tree-nest, becomes the confident claiming of a home.

Here, we go beyond mere comparison or allegory. The “proprietor” woodpecker, appearing at the tree’s window, singing from its balcony, a critical mind might call this an “exaggeration.” But the poetic soul will be grateful to Thoreau for expanding the image, giving us a nest that reaches the size of a tree.

A tree becomes a nest the moment a great dreamer hides in its branches. In Memoirs from Beyond the Grave, Chateaubriand shares such a memory: “I had built myself a perch, like a nest, in one of those willows: there, suspended between earth and sky, I would spend hours with the warblers.”

Indeed, when a tree in the garden becomes home to a bird, it becomes dearer to us. However hidden, however silent the green-clad woodpecker may be among the leaves, it becomes familiar. The woodpecker is no quiet tenant. And it’s not when it sings that we think of it, but when it works. All along the tree trunk, its beak strikes the wood with resonant blows. It often vanishes, but its sound remains. It’s a labourer of the garden.

And so, the woodpecker has entered my sound-world. I’ve turned it into a comforting image. When a neighbour in my Paris flat hammers nails into the wall late into the evening, I “naturalise” the noise. True to my method of making peace with anything that disturbs me, I imagine myself back in my house in Dijon, and I say to myself: “That’s just my woodpecker, working away in my acacia tree.”

Everything Flows

As part of Faire commun – a shared ecology project in Parc Rigot – least invites you to reflect on the rhythms that flow through living beings, places and time itself. “Faire commun” also means “making time together”: exploring how our lives align – or fall out of step – with the cycles that surround us. This text invites readers to attune to the world’s many pulses, imagining new forms of sensitive coexistence.

At Parc Rigot, students, researchers and artists came together to resonate with the land – an interdisciplinary and sensory exploration aimed at revealing the unique rhythms of the landscape, its lifeforms and its uses. By observing the park’s centuries-old oaks, its passers-by and its pond, they highlighted how each element vibrates at its own tempo – sometimes steady, sometimes chaotic – composing a shared, living score.

The word “rhythm” comes from the Greek verb rhéô, meaning “to flow”. In Greek philosophy, panta rhei (“everything flows”) captures the thought of Heraclitus of Ephesus, philosopher of perpetual change: all is in constant transformation, like a river whose waters move constantly, so much so that “one can never step into the same water twice” …

Water, indeed, is at the heart of our first experience of rhythm. Even before birth, we perceive sound through amniotic fluid: heartbeats, breath, blood flow. Only low, rhythmic sounds travel through this liquid medium. After birth, part of this water remains in us: the inner ear, still filled with fluid, senses the world’s vibrations. This original water holds a deep memory of rhythm and time within us. Perhaps that is why Rigot’s pond, nestled at the base of the park, acts as a sensory magnet: it draws the eye, attracts wildlife and becomes a focal point where human and non-human rhythms converge across the day.

Humanity has long sought to measure time. One of the earliest known instruments is a water clock (clepsydra) from the 14th century BCE, discovered in the Karnak Temple in Egypt. Two vessels, connected by a small opening, allowed time’s flow to be measured steadily. At Rigot, the oaks planted on the western side play a similar role: silent timekeepers, inscribing memory into their bark year after year.

In soundscapes little touched by human activity, most sounds follow predictable rhythms. Birdsong, the rustle of wind in leaves, the soft lapping of water – these recurring motifs are registered by living beings as familiar and non-threatening. Such regularity soothes and stabilises the soul. In contrast, abrupt noises – construction, crowds, traffic – disrupt sensory balance, triggering alarm. Auditory rhythm is thus a key element of perceptual stability.

Rhythm is essential to how every species hears. Neurons in the ear and brain activate only when sound frequencies align with a reference rhythm. In the 1960s, Hungarian researcher Péter Szőke slowed down birdsong to reveal its hidden complexity, unheard by the human ear. This attention to the invisible and the subtle informs the sensory work carried out in Parc Rigot: to listen, to slow down, to observe what often slips beneath the surface of perception.

Drawing: ©Anaëlle Clot.

For living beings, time unfolds on three levels: internal rhythm, synchronisation with environmental cycles and coordination with others. Internal rhythm is fine-tuned by external signals – zeitgebers (“time-givers”) – such as light, temperature and seasons. For migratory birds, the memory of thawing snow, the length of day and the behaviour of other species help determine when to depart for breeding grounds.

Time, then, is not solely personal, it is also social. In a beehive, nurse bees maintain a constant internal rhythm, while foragers adjust to the timing of flower openings. The coordination of these internal clocks generates a shared rhythm, or a collective time.

Human societies, too, maintain diverse and complex relationships with time. In many Indigenous cultures, time is tied to local rhythms of land, animals and landscapes. Among Sámi reindeer herders, for instance, the concept of jahkodat holds that each year is unique: migration depends on the snow thawing, pasture health and other shifting factors. “One year is not the sister of the next”, a Sámi proverb says: each cycle demands careful attention and constant adaptation.

Today, globalisation has dulled this seasonal sensitivity. Yet seasonality is not universal. Some regions know four seasons; others alternate between wet and dry. In Nagori, Ryoko Sekiguchi notes that Japan traditionally divides the year into 24 seasons, or even 72 micro-seasons. This refined sense of time shapes language itself, with words and haikus linked to precise moments, weaving culture, climate and expression together.

But so-called “objective” time is also a human invention. In Austerlitz, W.G. Sebald reminds us that while time is tied to the stars, it ultimately rests on convention. Even the solar day varies; to stabilise our clocks, we invented a “mean sun” – a fictional body whose steady motion serves as a reference.

The standardisation of time intensified in the 19th century with the advent of railways. To coordinate schedules, time zones were imposed, overriding the diversity of local times. The world entered an era of strict synchronisation, a standardisation that now coexists with the ecological and temporal dissonance we face.

For non-humans, life depends on a fine attunement between living rhythms and Earth’s cycles. Climate change is unsettling these balances. At Rigot, as elsewhere, seasons shift, temperatures rise, blooms and migrations fall out of sync, disrupting biological clocks. This breakdown threatens the reproduction, food sources and survival of many species. When life’s rhythms fall out of step with Earth’s cycles, the very balance of life begins to waver.

In the face of growing dissonance between human time and living time, Faire commun calls for a sensitive reorientation: to slow down, to listen, to live together. Parc Rigot becomes a shared learning ground, where we can explore new ways of inhabiting time, neither linear or productivist, but rather cyclical, porous, attuned to what grows, changes or disappears. By reconciling Earth’s many temporalities, this project sketches the outline of an inhabitable future.

Living Soil

Although we walk on it every day and it is essential to our food security, we rarely consider the importance of soil in our lives. What crucial roles does soil play in maintaining the balance of ecosystems? How can we protect it? And how can artistic practices help?

Below is an interview with Karine Gondret, a trained soil scientist and geomatician, HES-SO research associate and lecturer at the Geneva School of Landscape, Engineering and Architecture (HEPIA). Her research focuses on soil quality assessment and mapping.

What is pedology?

A branch of soil science, pedology focuses on the study of soils, i.e. the interactions between living organisms, minerals, water, and air that take place beneath our feet. In pedology, we examine everything that lies between the surface and the first, purely mineral layer, i.e. around 1.50 m deep in our latitudes. Beyond that, when only minerals remain, we enter the field of geology. The role of the pedologist is also to map the soil.

What is meant by good quality soil?

Broadly speaking, good quality soil is soil that is capable of performing the functions necessary for the survival of all living organisms and their environment. Several functions are very important, beyond the most obvious, that of food or biomass production. Soil infiltrates, purifies, and stores water, and recycles nutrients and organic matter. There is also the genetic reserve function, which is still seldom studied. Penicillin, for example, was discovered in the soil. So it’s crucial to protect our soils.

What parameters need to be taken into account to assess the quality of a soil according to its functions?

In general, the higher the organic content of soil, the better it is able to perform its functions. By organic, we mean all living things (earthworms, micro-organisms, bacteria, etc.) and all carbon-rich compounds derived from living things (corpses, excrement, roots, dead leaves, compost, root and bacterial exudates, etc.). Functioning soil is living soil, and much more!

There are several other essential parameters, such as soil depth, pH, texture, porosity, etc. Depending on the function, certain parameters will be more or less important. For example, the function of supporting human infrastructure (roads, buildings, etc.) will inevitably be detrimental to the biomass production function. That’s why politicians have to make choices about the functions they want to protect.

Why is the presence of organic matter in soils important?

Organic matter is the basic food source for the soil’s fauna and micro-organisms. It is continually broken down by soil life into nutrients that are accessible to plants via soil water. Organic matter also improves soil porosity. Porosity is essential for the proper development of life, as it allows nutrient-rich water, air, and roots to circulate. Without this porosity, exchanges are much less effective, and as a result, its functions are much less effective.

In addition, organic matter is capable of increasing the soil’s capacity to store water and of mitigating flooding in towns downstream. It can also retain nutrients and pollutants through its electrical properties. Finally, organic matter that is stabilised in the soil contains around 60% of carbon, and the more it increases in the soil, the more we limit global warming, because all the carbon that is not stored in the soil goes into the atmosphere in the form of CO2.

We’ve talked about what good soil is for humans, but what about the “more than human” world?

As defined by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), soil performs functions that are essential to humankind. In truth, these functions are essential to the proper functioning of ecosystems, and humans simply benefit from them. For example, many pollinators spend part of their life cycle in the soil. These pollinators make it possible to obtain fruit and feed wildlife, which is beneficial for natural environments. But this fruit also benefits humans within agricultural and economic infrastructures, when it is sold. Humans and the environment are deeply interconnected, although we tend to forget this. Finally, compared to about fifty years ago, the organic matter content in most agricultural soils has halved. This means that these soils are becoming increasingly less effective at performing the functions they provide for us.

Images: Thierry Boutonnier, Comm’un sol, 2024. Photo: ©Eva Habasque.

As part of the Faire Commun research project, artist Thierry Boutonnier devised a method for sensitively assessing the quality of the soil in Parc Rigot. He organised a picnic on a long organic cotton tablecloth, which was then cut into pieces and buried in different areas of the park. After a few months, the tablecloth was dug up, and the amount of fabric consumed thanks to the soil’s bioactivity provided concrete information about its characteristics. What did you observe?

We haven’t yet finished carrying out the analyses in Parc Rigot, but we’ve observed the soil’s capacity to degrade organic matter through this experiment. In the soil, micro-organisms release enzymes that degrade organic matter (here the cotton tablecloth). We also observed that these micro-organisms were not all equally active: in some areas of the park, the organic matter was broken down very efficiently, while in other areas, the process was much slower. This means that in these areas, there are fewer nutrients available for the plants that grow.

People often don’t realise that there is diversity of soils, even in small areas. In the city, as in Parc Rigot, this diversity is even more marked because humans have had such a strong impact on the soil. There have been many interventions – areas have been completely renatured, others stripped, or artificially added – and this has led to a juxtaposition of very different soils. The challenge is to identify the areas that really work, and protect them.

Is it possible to improve soil quality?

When soil doesn’t have the necessary quality for a given function, we can intervene to improve it, for example by adding organic matter or by decompacting it (in compliance with the OSol ordinance in Switzerland). Nevertheless, soil quality only improves very slowly; sometimes it takes several human generations, sometimes improvement is impossible. Soil is a non-renewable resource, as it takes a very long time to create: it is said to increase by an average of 0.05 millimetres per year. In very steep areas, it even becomes thinner and thinner.

It can also deteriorate rapidly. It looks solid and is thought to be immutable, but nothing could be further from the truth. Even when we’re trying to improve its quality, we have to be very careful, because every intervention on the soil leads to its deterioration. It’s a delicate process that doesn’t always work – we’re still experimenting.

Soil is at the intersection of physics, biology, and chemistry. It’s a complex world, and by no means do we know everything about it. So it’s all the more important to protect it, because it’s where all plant nutrients are found, and as they develop, they form the basis of the diet of all mammals. The soil is truly the place where life is created.

Autumn in the Garden

The gardener, hands immersed in the soil and in constant contact with plants, might seem to have an idyllic job in the face of urban hassles. But, according to Karel Čapek, nothing could be further from the truth. In his book The Gardener’s Year (1929), Čapek describes the gardener’s problems and tribulations in the face of frost, drought, and the overweening ambitions of small urban gardens. His wonderfully written tale, imbued with irony, offers a reflection on the complexity of human nature, not without a touch of humour and levity. Below is a short extract from the book.

We say that spring is the time for germination; really the time for germination is autumn. While we only look at nature it is fairly true to say that autumn is the end of the year; but still more true it is that autumn is the beginning of the year. It is a popular opinion that in autumn leaves fall off, and I really cannot deny it; I assert only that in a certain deeper sense autumn is the time when in fact the leaves bud. Leaves wither because winter begins; but they also wither because spring is already beginning, because new buds are being made, as tiny as percussion caps out of which the spring will crack. It is an optical illusion that trees and bushes are naked in autumn; they are, in fact, sprinkled over with everything that will unpack and unroll in spring. It is only an optical illusion that my flowers die in autumn-; for in reality they are born. We say that nature rests, yet she is working like mad. She has only shut up shop and pulled the shutters down; but behind them she is unpacking new goods, and the shelves are becoming so full that they bend under the load. This is the real spring; what is not done now will not be done in April. The future is not in front of us, for it is here already in the shape of a germ; already it is with us; and what is not with us will not be even in the future. We don’t see germs because they are under the earth; we don’t know the future because it is within us. Sometimes we seem to smell of decay, encumbered by the faded remains of the past; but if only we could see how many fat and white shoots are pushing forward in the old tilled soil, which is called the present day; how many seeds germinate in secret; how many old plants draw themselves together and concentrate into a living bud, which one day will burst into flowering life—if we could only see that secret swarming of the future within us, we should say that our melancholy and distrust is silly and absurd, and that the best thing of all is to be a living man—that is, a man who grows.

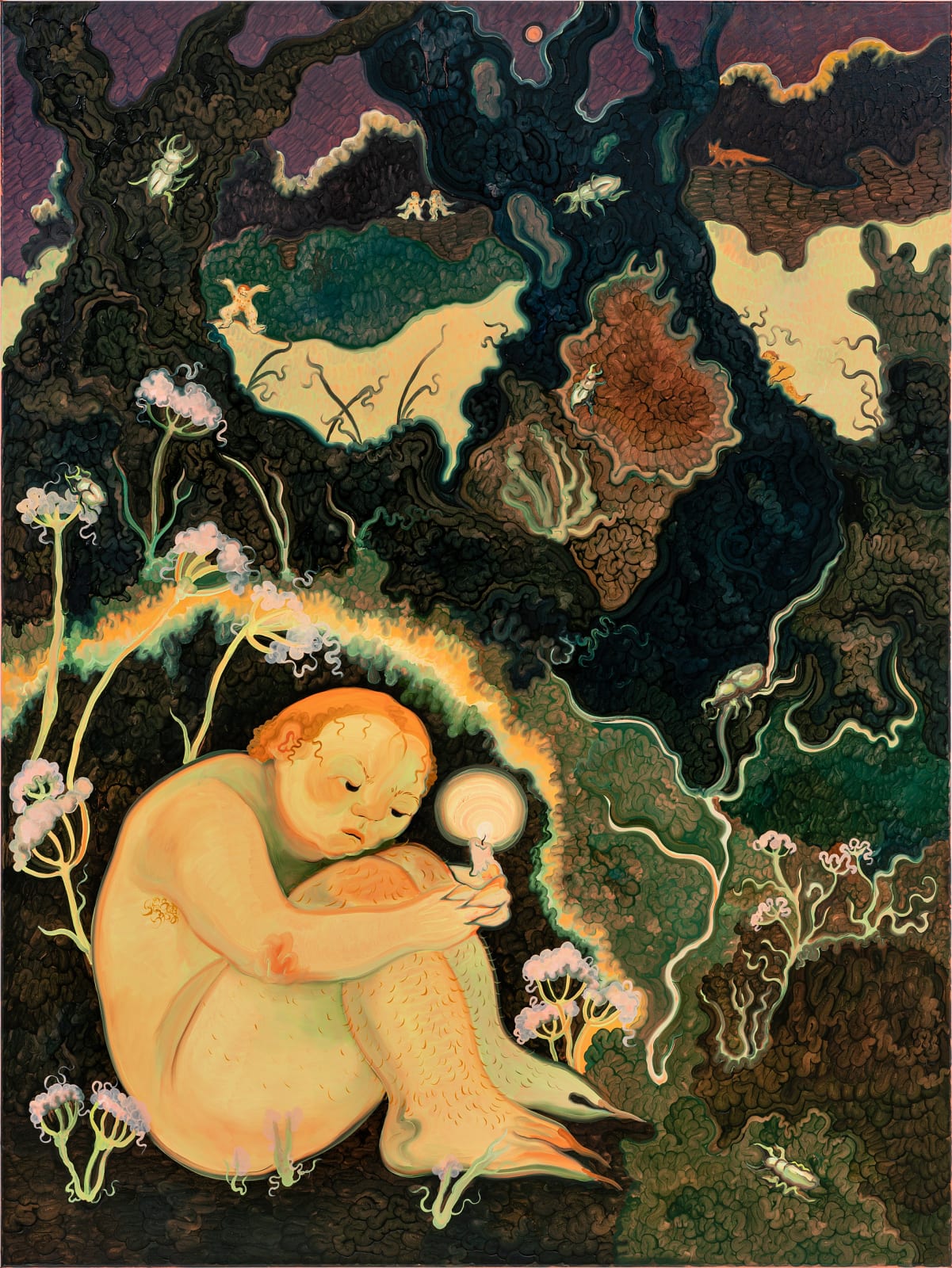

Image: Natália Trejbalová, Few Thoughts on Floating Spores (detail), 2023.

Courtesy of the artist and Šopa Gallery, Košice. Photo: Tibor Czitó.

Ô noble Green

O noble Green, rooted in the sun

and shining in clear serenity,

in the round of a rotating wheel

which cannot contain all the earth’s magnificence,

you Green, you are wrapped in love,

embraced by the power of celestial secrets.

You blush like the light of dawn

you burn like the embers of the sun,

O most noble Viriditas.

This magnificent hymn to the creative power of “green” is a responsory written and set to music by one of the most brilliant minds of medieval Europe: Hildegard of Bingen, a Christian saint and mystic who lived in the Rhineland in the early 12th century. The tenth daughter of a noble family, from an early age Hildegard was subject to visions and migraines, and for this reason she was destined for the convent already at the age of thirteen. She would only confess and publicly describe her visions at the age of forty-three, prompted by a divine order; a few years later, she founded the monastery of Bingen, of which she was abbess.

Hildegard’s merits are countless: she is the first Western female composer of whom we have written testimony, and her body of music is the most substantial of the era in which she lived to have come down to us. She was an excellent naturalist: her mighty treatise Physica includes 230 chapters on plants, 63 chapters on elements, 63 chapters on trees, and many more on stones, fish, birds, reptiles, and metals, enriched with indications of their medicinal properties: for this reason, some consider her the founder of naturopathy. Her homilies and speeches, imbued with a form of revolutionary vitalism that was unknown to the ecclesiastical thinking of the time, were encouraged and even published with the support of powerful popes and prelates such as Bernard of Clairvaux – a truly exceptional fact in the profoundly misogynistic context of medieval Europe.

Hildegard, however, encountered some difficulty in describing her visions: “In my visions, I was not taught to write like the philosophers. Moreover, the words I see and hear in my visions are not like the words of human language but are like a burning flame or a cloud moving through the clear air.” How do you convey something that cannot be spoken? How do you give voice to new concepts, unknown to the theologians and wise men of the time? How do you criticise the very structure of current thought? Hildegard did not choose the easy way, but decided to invent a new language, which she called Ignota Lingua and which is considered one of the first “artificial languages” ever created (Hildegard is in fact considered the patron saint of Esperanto). Her “dictionary” is actually a glossary of 1011 words, mostly transcribed into Latin and medieval German with the help of a scribe.

Image: Hildegard of Bingen, The hierarchy of angels, sixth vision of the Scivias manuscript.

Among many wonderful linguistic inventions, the concept of viriditas recurs in her writings. Scholar Sarah L. Higley attempts a translation: “viriditas, ‘greenness’ or ‘greening power’, or even ‘vitality’, is associated with all that partakes of God’s living presence, including blossoming nature, the very sap (sudor, ‘sweat’) that fills out leaves and shoots. It is (…) closely associated with humiditas, moisture. Hildegard writes (…) that ‘the grace of God glitters like the sun and sends forth its gifts variously: one way in wisdom (sapientia), another in viridity (uiriditate), a third in moisture (humiditate). In her letter to Tenxwind she compares the virginal beauty of woman to the earth, which exudes (sudat) the greenness or vitality of the grass. The Virgin Mary, of course, is viridissima virga, the ‘greenest branch,’ in Hildegard’s Symphonia. Aridity, on the other hand, represents incredulity, a lack of spirituality, the abandonment of the virtues in their greenness: that which withers and is consumed at the moment of Judgement.

For the inner eye of the mystical naturalist, capable of scrutinising the invisible in the visible, the whole of creation is a flow of divine, gushing green sap. Hildegard attached great importance to the colour green, a symbol of vigour, youth, creative power, efflorescence, fructification, fertilisation, and regeneration. Celebrating greenness for Hildegard is recognising that we are part of a whole, without separation, and serves to maintain the cohesion between soul and body. This radical thinking requires new words, new ways of thinking: inventing a language is an act that helps us understand that everything can be called into question, everything can be imagined from new premises.

Below is a selection of words of the Ignota Lingua from the chapter on trees (translated to English by Sarah L. Higley): an invitation to (re)think everything, starting with the most common words.

Lamischiz — FIR

Pazimbu — MEDLAR

Schalmindibiz — ALMOND

Bauschuz — MAPLE

Hamischa — ALDER

Laizscia — LINDEN

Scoibuz — BOXWOOD

Gramzibuz — CHESTNUT

Scoica — HORNBEAM

Bumbirich — HAZEL

Zaimzabuz — QUINCE

Gruzimbuz — CHERRY

Culmendiabuz — DOGWOOD

Guskaibuz — WINTER OAK

Gigunzibuz — FIG

Bizarmol — ASH

Zamzila — BEECH

Schoimchia — SPRUCE

Scongilbuz — SPINDLE-TREE

Clamizibuz — LAUREL

Gonizla — SHRUB?

Zaschibuz — MASTIC

Schalnihilbuz — JUNIPER

Pomziaz — APPLE

Mizamabuz — MULBERRY

Burschiabuz — TAMARISK

Laschiabuz — MOUNTAIN ASH

Golinzia — PLANE TREE

Sparinichibuz — PEACH

Zirunzibuz — PEAR

Burzimibuz — PLUM

Gimeldia — PINE

Noinz — CHRIST’S THORN

Lamschiz — ELDER

Scinzibuz — SAVIN SAVINE

Kisanzibuz — COTTON TREE

Vischobuz — YEW

Gulizbaz — BIRCH

Scoiaz — WILLOW

Wagiziaz — SALLOW

Scuanibuz — MYRTLE

Schirobuz — MAPLE

Orschibuz — OAK

Muzimibuz — WALNUT

Gisgiaz — CALTROP

Zizanz — BRIAR

Izziroz — THORN TREE

Gluuiz — REED

Ausiz — HEMLOCK

Florisca — BALSAM

The Multiciplity of the Commons

Swiss philosopher Yves Citton’s areas of research range from literature to media theory and political philosophy. We met him as part of our Faire Commun project to discuss a central theme of our research: the commons. Below is a transcript of part of his talk.

I’d like to introduce the “commons” by trying to qualify a certain image – which isn’t wrong, but quite partial – of the commons as pre-existing human appropriation. According to folklore, the Earth and its goods were shared by all animals and all featherless bipeds like ourselves. Then, according to Rousseau’s second discourse, human appropriation became the source of all evils.

This means that the commons are given as they are by nature. It’s true that the air we breathe, for example, wasn’t created by humans so that they wouldn’t die of asphyxiation: on Earth there is air, and we humans benefit from it. It’s a certain layer of the commons that we enjoy naturally, even if we don’t know exactly what nature means.

We can also say that air and water are quite similar commons. On Earth, there’s salt and fresh water, which is drinkable. But if you think about the reality of water today, the water we drink is more or less natural water. We know that it can contain chlorine, that it flows through pipes. Hence, to my mind, water isn’t at all a natural commons. It’s the result of an infrastructure, which can be public, private, or associative; it can be democratic or subject to capitalism. It’s mediated by the community or public institutions. In order to distinguish between public and private commons, I’d call this case public – a government has intervened, made regulations, and financed the pipes.

It’s still a commons, but one that has been constructed by humans, legislation, and political processes. Most of the time, when we talk about the commons today, these elements are inevitably involved. Even forests no longer look like they did before humans brought domesticated species and technologies into them. So I think it’s more realistic to say that the commons include a human artificialisation and preservation dimension. We don’t necessarily need to take care of the air – it’s enough not to pollute it – but we do need to preserve water, pipes, and infrastructures.

It’s interesting to consider another, slightly different model of the commons, i.e. language. Language didn’t precede humans, there was no French language 300,000 years ago; it isn’t an institution, nor an infrastructure regulated by a state that cares for and maintains it. French resides both within and between us. To my mind, it’s the most bizarre and extraordinary model of the commons, existing only because we own it: if all the people who speak French disappeared, there’d be no more French. (That’s without taking into account books written in French, which would remain of course). Knowing where a commons lies, whether it’s artificial or public, is no easy task. For me, what language highlights about the commons is the fact that it can exist without official regulation. The Académie française did not create the French language. Language is reproduced through culture and through children talking to their parents. It’s a commons: it’s neither totally public nor totally private.

Image: Mattia Pajè, Il mondo ha superato se stesso (again), 2020

The French language, air and water are elements that are necessary to our survival, and we’re grateful that they’re available to us: we can define them as positive commons. Conversely, there are negative commons, which are a continuation and a reversal of the latter. Researchers Alexandre Monnin, Diego Landivar, and Emmanuel Bonnet use the term “negative commons” to refer to nuclear waste, to cite only the most telling example. Whether a nuclear power station has public or private status doesn’t change the fact that the resulting waste becomes a collective problem for hundreds of thousands of years to come. It’s clear that nuclear waste is a commons, just as plastic and the climate are. Indeed, the climate, like water, is becoming an element that needs to be maintained if it’s to remain liveable. Some negative commons are therefore blending in with commons that were traditionally seen as positive. These negative commons pose a major problem: they feed our lives (the nuclear power station feeds my computer, which allows me to communicate) but they harm our living environments. Feeding and harming are seen as two sides of the same coin, at the same time. Nuclear energy provides me with electricity but harms future generations through the production of radioactivity.

If we develop this idea further, we can see finance as a good example of a negative commons: finance feeds our investments and the state budget but pollutes our environments by pushing to maximise profits at the expense of environmental considerations. How do we get out of this? How can we dismantle finance? It’s even more interesting to ask whether universities are not a negative commons: knowledge is developed, and research carried out, but the way universities operate can be toxic, with some teachers taking advantage of their power over their students, for example. There’s also bureaucracy that prevents us from doing good work at the same time as framing and structuring that work. There are toxic elements that need to be dismantled, but it’s not easy because they feed us. The intellectual exercise of projecting a negative commons hypothesis onto different subjects is therefore quite revealing.

There’s also the concept of undercommons, a term defined by Afro-American poet and philosopher Fred Moten and activist and researcher Stefano Harney. This term is based on the political ideas of the Black Radical Tradition in the United States. The over-representation of black people, particularly black men, in prisons in the United States today is dramatic, and there’s a continuity between slavery a few centuries ago and racial domination in this country today. The people who emerged from the slave holds were never considered as individuals in their own right. They therefore had to develop other modes of sociality, alternatives to the individualistic socialisation of the homo economicus, the small businessman, the white bourgeois. The communities that were threatened with lynching until a few decades ago and are now victims of police violence, live in conditions of marginalisation or at least do not enjoy the privileges that you and I, as white people in Switzerland or France, have been able to enjoy. These people have therefore developed an alternative, underground form of socialisation: a somewhat paralegal or semi-legal form of solidarity, since US law is made by white people for white people. Instead of seeing this form of solidarity as illegal, it might be seen as a different form of solidarity, outside the law, but one that is worthy of consideration and study. It enables ways of living that feed the commons, even if they’re less visible. And it could prove crucial for all of us: the infrastructures that sustain our luxuries and our forms of economic and social individualisation, as we know them today, may not last indefinitely. It would therefore be in our interests to familiarise ourselves with this form of “survival solidarity”. And of course, before doing so, it’s important to denounce and fight against the persistent oppression that weighs on marginalised populations.

I had the opportunity to work with Dominique Quessada, who came up with the idea of writing the term “commun” (commons in French) as “comme-un” (literally “as one”): his idea being that the commons belongs to everyone and to no one at the same time. The very fact of talking about the commons perhaps presupposes that the term is established, that there are people who see it as a real possibility, and that behind the dissolution of identity and property, the commons is something in which everyone can participate: it’s a plural, it’s neither mine nor yours. Above all, to write it “comme-un” suggests that the unity (of a certain people, of a community) that is often thought of as inherent to the commons is perhaps no more than “acting-as-if we were one”. Faced with the commons, we act “as one”, but we remain diverse, different, and sometimes antagonistic to one another.

Behind the commons there are always two concepts. First of all, there is the principle of unity: who are those who speak of a “commons”? On what do they base themselves? In reality, they can only defend a commons because they’re already united. Secondly, the commons is always a collective fiction: calling something a “commons” means that it is considered as such and thus develops characteristics of a commons. A public park is a public park because it is declared to be one. Thanks to this label, it’s possible to do things in this park that would otherwise have been impossible. But this remains a temporary fiction: a change of regime, a sale, an occupation of the site can always happen. In short, writing “comme-un”, or “as-one”, with a hyphen means asking two questions. Firstly, what is this unity, however heterogeneous, that allows us to say that there is a commons? Secondly, what is the fictional element, the dynamic that allows us to forge a concept that doesn’t exist? The imaginary dimension of the commons always remains central to its defence.

Experiencing the Landscape

In everyday language, the term “landscape” encompasses a variety of notions: it can refer to an ecosystem, a beautiful view, or even an economic resource. However, the complexity of the term can be better understood and approached through the concept of “experience”.

Experience is something that brings us into contact with the outside, with otherness: in this context, the landscape is no longer seen as an object, but rather as a relationship between human society and the environment. An experience is also something that touches us emotionally, that moves and transforms us. Viewing a “landscape” as such helps us realise how much it gives meaning to our individual and collective lives, to the extent that its transformation or disappearance leads to the destruction of sensitive markers of existence in the lives of its inhabitants. Experience can also be seen as a form of practical knowledge or wisdom. It is the kind of knowledge that is acquired by living in a place, which makes the people who inhabit a landscape its experts. Finally, experience is also a form of experimentation: this is the active aspect of our relationship with the world, enabling us to discover and create new knowledge and to bring to life what is yet only potential.

We might take these reflections a step further and argue that human beings live off the landscape—a statement that may seem hyperbolic, but that makes sense if we pay close attention. Indeed, the landscape is the source of our food: we live in the landscape and the latter activates representations and emotions within us. Our relationship with the landscape is dynamic: by changing it, we also change ourselves. It is therefore impossible to avoid entering into a relationship with the landscape. The very choice of ignoring and not ‘experiencing’ a landscape can have practical and symbolic consequences.

It is on the basis of these observations that Jean-Marc Besse wrote La Nécessité du Paysage (the Necessity of the Landscape): an essay on ecology, architecture, and anthropology, as well as an invitation to question our modes of action. In it, the French philosopher warns us against any action on the landscape: an attitude that places us ‘outside’ the said landscape, which, as mentioned above, is simply not plausible. Acting on a landscape means fabricating it, in other words starting from a preconceived idea that ignores the fact that the landscape is a living system and not an inert object. “Acting on therefore involves a twofold dualism, separating subject and object on the one hand, and form and matter on the other.”

So how might we escape this productive yet falsifying paradigm? Besse suggests a change of perspective: moving from acting on to acting with, recognising “that matter is animated to a certain extent” and envisaging it “as a space of potential propositions and possible trajectories”. The aim, in this case, is to interact “adaptively and dynamically”, to practise transformation rather than production. Acting with means engaging in ongoing negotiation, remaining open to the indeterminacy of the process, and being in dialogue with the landscape: in a word, collaborating with it.

Georg Wilson, All Night Awake, 2023

Acting with the soil

The “abiotic” dimension of soil is addressed, among other disciplines, by topography, paedology, geology, and hydrography. However, from a philosophical point of view, soil is simply the material support on which we live. This is where we construct the buildings we live in and the roads we travel on, and it is the soil that makes agriculture possible, one of the oldest and most complex fundamental manifestations of human activity. This “banal” soil is therefore in reality the focus of a whole series of essential political, social, and economic issues, and as such it raises fundamental questions. What kind of soil, water, or air do we want? The environmental disasters linked to the climate crisis and soil erosion or the consequences of the loss of fertility of agricultural and forest land call for collective responses that draw on both scientific knowledge and technical skills, as well as many political and ethical aspects.

Acting with the living

The landscapes we inhabit, travel through, and transform (including the soil and subsoil) are in turn inhabited, travelled through, and transformed by other living beings, animals and plants. In his essay Sur la Piste Animale (On the Animal Trail), philosopher Baptiste Morizot invites us to live together “in the great ‘shared geopolitics’ of the landscape”, by trying to take the point of view of “wild animals, trees that communicate, living soil that works, plants that are allies in the permacultural kitchen garden, to see through our eyes and become sensitive to their habits and customs, to their immutable perspectives on the cosmos, to invent thousands of relationships with them”. To interpret a landscape correctly, it is necessary to take into account the “active power of living beings” with their spatiality and temporality, and to integrate our relationship with them.

Acting with other human beings

A landscape is a “collective situation” that also concerns inter-human relations in their various forms. A landscape is linked to desires, representations, norms, practices, stories, and expectations, and it draws on emotions and positions as diverse as people’s desires, experiences, and interests. Acting with other human beings means acting with a complex whole that includes individuals, communities, and institutions, and drawing on the practical and symbolic—in a continuous process of negotiation and mediation.

Acting with space

Considered through the tools of geometry, space is an objective entity: its dimensions, proportions, and boundaries can be satisfactorily described. However, the space of the landscape cannot be reduced to measurable criteria. In reality, it is an intrinsically heterogeneous space: “locations, directions, distances, morphologies, ways of practising them and of investing in them economically and emotionally are not equivalent either spatially or qualitatively”. Interpreting the space of the landscape correctly therefore means remembering that “numerical” and “geometric” measurements are necessarily false, and that the set of geographies (economic, social, cultural, or personal) that make it up are neither neutral, nor uniform, nor fixed in time.

Acting with time

When we think of the relationship between landscape and time, the first image that springs to mind is that of the earth’s crust and the geological layers that make it up, or that of archaeological ruins buried beneath the surface. In short, we imagine a sort of tidy “palimpsest” of a past time, with which all relations are closed. The time of the landscape, however, should be interpreted according to more complex logics: we need only think of the persistence of practices and experiences in its context, and the fact that landscape destruction is never total: rather, it is transformation. What’s more, the time of the landscape also includes non-human time scales, such as geology, climatology, and vegetation. They are temporalities to which we are nonetheless closely linked. Thus, in reality, the landscape remains in constant tension between past and present.

“Our era,” Jean-Marc Besse concludes, “is one of a crisis of attention. […] Landscape seems to be one of the ‘places’ where the prospect of a ‘correspondence’ with the world can be rediscovered […]. In other words, the landscape […] can be seen as a device for paying attention to reality, and thus as a fundamental condition for activating or reactivating a sensitive and meaningful relationship with the surrounding world”, in other words, the necessity of the landscape.

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue) is an artistic and urban ecology project created by Thierry Boutonnier and Eva Habasque, that involves citizens in the design, creation and maintenance of an orchard in Onex (Geneva, Switzerland). In this video, director Simon David has gathered footage from the early stages of this project.

The Gesamthof recipe: A Lesbian Garden

Hedera is a collective observation of the overlap between postnatural and transfeminist studies.

Each volume gathers insights related to these topics in the form of conversations, essays, fiction, poetry, and artist content. Hedera is a yearly publication, and its first volume features “The Gesamthof Recipe: A Lesbian Garden” written by artist Eline De Clercq.

The Gesamthof is a non-human-centred garden, it is a garden without the idea of an end result and it is about working towards a healthy ecology. This recipe shares how we garden in the Gesamthof.

Rest, observe.

Start with ‘not a thing’, it is the quietude before one begins. Rest as in ’not to take action yet’. I find this a good begin, it has helped me many times. When I plan to work in the garden I put on my old shoes, take a basket with garden tools and the seeds to sow, and I open the gate and step into the garden and - stop. Not to act at once, but to wait a moment before beginning gives me time to align myself with the soil, the plants, the temperature, the scents, images and sounds. I look at the birds, the snail, the beetle on a leaf. I walk along the path and greet the plants and stones. Like me, in need of a moment, they too need to see who entered the garden. I know the plants can see me because they can see different kinds of light and they grow towards light and they see cold light when I stand in front of them casting my shadow on them. They can see when the sunlight returns and I moved on. This is the first connection with the garden: to think like a gardener-that-goes-visiting. Donna Haraway writes about Vinciane Despret who refers to Hannah Arendt’s Lectures on Kant’s Political Philosophy; ‘She trains her whole being, not just her imagination, in Arendt’s words “to go visiting.”’ all from the book Staying With The Trouble (see the reading list below). Sometimes it is all I do, and time passes, for an hour and more I feel truly alive with listening, feeling, scenting and seeing. I can taste the season.

Your senses & your mind.

To feel as well as to think along with nature. This is perhaps the hardest to explain, but this is the way I learned to garden from when I was helping as a volunteer in the botanical garden in Ghent. While there is a lot to learn and to remember: you can look it up most of the time. There are plenty of books on what kind of plant likes to live in what kind of conditions. Those facts are easy to find. For me, the rational explanation comes in the end, like a litmus test to see if a theory works. I like to begin with experiencing things: feeling the texture of a leaf, noticing the change in temperature when it’s going to rain, comparing soil by rubbing it between your fingers, smelling soil, plants, fungi and so on. Senses connect us to all kinds of matter in a garden and they help one to become part of the garden. Donna Haraway writes about naturecultures, an interesting concept to rethink how we are part of nature and how the dichotomy of nature and culture isn’t a real contradiction. It is an argument to stop thinking as ‘only human’ and start becoming a layered living togetherness. It’s in our best interest to feel nature again with our senses. At the same time, be aware that many plants are poisonous and/or painful, they might hurt you so don’t trust your instincts too much without consulting facts.

Gesamthof, a non-human-centred garden.

The patch of soil I consider as the shared garden, the Gesamthof, is part of a planet full of bacteria, protista, fungi, plants and animals and all of these enjoy being in the garden too. I try to give the fungi some dead wood to eat, and I don’t use herbicides and pesticides while caring for the plants. This is kind of obvious, it’s basic eco gardening, but it also concerns the benefit of the entire garden. The important question is: who is getting better from this? When I count in birds, insects, plants and fungi and the needs they have to survive in a city, then a small garden is for the benefit of all of these and the ruined artichoke isn’t much of a disaster, many big and small gardeners enjoyed being with the artichoke, drinking the nectar, eating the leaves, weaving a web between the dried stalks. Thinking of all us gardening together changes the purpose of the garden, it’s no longer focused on humans only. Often I see a seedmix for bees in the garden centre, but every garden has a different relation to bees, sometimes with solitary wild bees living of a single plant species not having any interest in a human selected seed mix with a colourful flowers display. The question “Who is getting better from this?” stops me buying things for my pleasure and teaches me to be happy when a healthy ecology is establishing.

Thinking like this has made me question the situation of indoor plants. If they could chose between living inside a house in a cold country or being outside in a warm location, wouldn’t they prefer to sense the sunset and feel the wind in their leaves? Am I keeping plants in the house for my own benefit? Would plants grow in my house if I didn’t water them and look after their soil? Should I put plants in places where they naturally wouldn’t grow? I have decided not to buy new plants for in the house, I will care for the ones I am living with as good as I can. Does the garden end at the door? Or do I live in the garden too?

The diversity of city life in a garden.

The opposite of local wild nature is not a foreign plant, but a cultivated plant. The garden combines native plants from many continents, I grow African lilies next to stinzen flowers and local wild plants; they get along well. I’m not a puritan who wants to grow only one colour of flowers or only authentic plants, I see the garden more like a city where we arrive from all corners of the world. Plants don’t know borders, they don’t care for nations, if they like the place they’ll grow happily. But humans don’t always know what they are planting and we build so much & take away so many plants and replace the green in our gardens with other varieties, often cultivars that don’t interact with local species. A cultivar is the opposite of a wild plant, a cultivar is selected for a quality liked by humans but not always in regards to the ecology with other species. Some cultivars are great plants, they are strong and beautiful and interact in symbiosis with the rest of nature. But some cultivars blossom at the wrong time to attract insects, or they don’t provide anything for the others to interact with. In other words, they are planted to be pretty and not to take part of a wholesome nature. Because of these cultivars we are rapidly losing authentic genomes of plants that are important to preserve nature. When you have a garden that is designed and planted with only these kind of cultivars you don’t invite nature in. You might just as well have plastic flowers. The opposite is to care very much for the diversity of ‘pocket’ nature, what was growing in this pocket of the world, and to try to find old species specific for this area that have been around for thousands of years, and have become an important sustainable link within the local ecology of insects, plants, fungi and other living beings. I let the weeds grow in the garden to support the network of insects needing those plants, and birds needing the insects, and local plants needing these insects and birds as well and so on and so on. The gardens in a city are like corridors, they connect insects, plants and fungi into a greater network that is necessary to sustain these species. While we see walls and hedges around a garden, and we might think of it as our island, it is part of a larger green archipelago where plants, birds, insects and others are not hindered by walls. Every city has only one garden made up of all these green islands just a few streets apart.

We shouldn’t break this chain of connected nature by losing our interest in local wild plants, often seen as uninvited weeds and taken for granted, they are very important in a diversity that expands with every living species. Since we’re living in a time of mass extinction & losing multiple species every day, all the things we can do count and in a garden we can let nature in. Sometimes I buy organic local plants from small nurseries to support their effort for conservation. But there is very little money involved in the Gesamthof. When I started to work in the garden I got many plants, seeds and cuttings for free and in return I also like to give away sister-plants so the Gesamthof lives on in other gardens. This is how plants from all over the world became part of the Gesamthof, and they all are very important in the diversity of the garden. There are Spanish bluebells and a Chinese Wisteria that were planted by the monks from the monastery a long time ago, they survived decades of neglect, there are Evening Primroses that most probably arrived on the wind from neighbouring plots and there are colourful tulips, both wild and cultivated that attract all kinds of human and non-human visitors.

The garden will help you.

This is the strangest thing, but since I’m working in the Gesamthof, plants have arrived from all kinds of places, they have often been given to me for free. Also garden materials, pots & books seem to come without much effort. They arrive from lots of generosity from others. I work in the garden, but not to create ‘my garden’, I see the garden as its own entity and I’m ‘the one with arms and legs’ who can help where needed. Many other living things help as well. Wasps have been eating the aphids, Cat’s Foot (Glechoma hederacea) is keeping my path free from weeds and the Titmice eat the spiders that make a web on the garden path (thank you, I don’t like walking into spider webs). I’m one of the garden critters (a word I borrow from Donna Haraway, critter isn’t as attached to creation as creature is) and I love seeing the other critters thrive at their work. I’m not doing this alone. While I do put in a lot of work, I see it as a part of my artistic practice. Gardens are often not seen as an artwork, but to do research, to add a different perspective, to engage with the soil, water and living beings, to build a different kind of place and share this as a public work is very much how I see art work. Art can be more than making and showing things, it can be interaction, awareness and sharing too. The Gesamthof works without a financial set up, it is thriving by generous neighbours who share their plants, seeds, helping hands and advice. This garden is giving more than it costs.

Don’t make a garden design.

This might sound counter intuitive, but being in the garden very often, one should know what the garden needs and that should be enough of planning. The usual garden plan is often seen as to give shape to the idea of an ideal garden, with a sketch of what to plant where, what colours to combine, where the path should be and in what material and so on. It would mean to put oneself above all else as the creator, and it means setting oneself a goal to work towards, with in the end a ‘beautiful garden’. I don’t think gardens should be ‘made’ beautiful, just like women shouldn’t be judged on a scale of beauty. It’s a binary opposition, a way of thinking that leads to a lot of suffering both in and outside of the garden. Instead let the garden take the lead and follow in its steps. You find a plant that likes a sunny area, put it in the sunny part of the garden and it will thrive. Do you have a lot of bare soil in the shady area and you don’t know what to do with it? Look up shady plants, find a nice variety and let it grow in your garden. Do you need a path between the plants? Add the material that works best in that place (for instance a forest kind of material would be tree bark, and recycled materials also make excellent paths). This way you’re growing a cultivated wild garden that will be beautiful all by itself just like nature is. Use creativity in how you arrange stones along a path, in how you support plants that will fall over, in how to add water and feeding stations, in creating fine labels, in making drawings that will later on help you to remember what you planted where… there is lots of room for creativity.

Intersectionality & botany.

The connection between botanical classification systems and people classification systems illustrates how the same mode of thinking is applied to both our gardens and us as people. Botany is full of anthropocentrism and it is not bad to be aware of this, the lesbian garden reframes this use of gardens. Suddenly the invisible norm of who usually benefits from gardens is no longer in place. ‘Lesbian’ means nothing if it is not connected to racialized people, to class differences, to living with disabilities, to age and all the other aspects gathered in Kimberlé Crenshaw’s intersectional theory. To put intersectionalism into practice means asking the ‘other question’: who benefits from this garden?

- Bees opens up the discussion on native plants, their genomes and diversity in gardening.

- Plants opens up the discussion of the colonial past, systems of economics, and who has a ‘right’ to extract.

- An audience that visits art spaces (the Gesamthof is accessible trough the Kunsthal Extra City) opens up the question of class, inviting the ‘other’ in, LGBTQIAP+ friendly spaces etc.

- Me opens up the question of access & responsibility that comes with privilege.

To ask the other question means that we are aware of others. Is the Gesamthof appropriate for children? Should it be? Should we take out all the poisonous plants, the pond, the bees hotel etc if we want children to be safe? There is a fence around the Gesamthof to keep wandering people out, because the garden is certainly not safe for everyone and not everyone is safe for the garden.

Atemporal gardening.

Every place carries a past into its future. The past is not a distant island, it’s very much with us in this thick present (again Donna Haraway’s words, the thick present is like a composted layered presence). In my garden I don’t want to be blind for what is present from the colonial past. It takes effort to find out how all of this is linked, how the history of botanical gardens is woven into to the need for classifying. It is hard work to learn about colonialism and gardening because it’s not as clearly visible as for instance plantations and slavery are linked to cotton and coffee. A garden is often more like a collection of plants bedded into a designed space and the colonial past is not a comfortable topic in garden programs. It takes visiting the past to find out what is here today. For me it meant going to the botanical garden in Meise and looking at the plants brought back from colonies. It also meant digging in the past of the Gesamthof’s location in the monastery, who was gardening here before me? How can I work with ecology towards a better understanding?

Note: People suffer from plant-blindness (J. H. Wandersee and E. E. Schussler, publication ‘Preventing Plant Blindness’ from 1999), it means we don’t see the plants that we don’t know and by giving garden tours one can share the awareness of this cognitive bias. In a lesbian garden the cognitive bias rings a bell, without representation people have a hard time discovering what is different about them. Many lesbians don’t know that they are a lesbian when they grow up, and they see themselves through the norm of a heterosexual society while a part of who they are remains empty for themselves. Like plant-blindness, this abstraction of a norm can be countered by looking at the differences as positive characteristics.

Ongoing change.

A garden is a nice form of art & activism, it is a healthy activity that helps to relieve stress and anxiety. It is working towards change by educating one’s self and each other, it is becoming aware of nature and changing our way of thinking. It is pleasant: the scent, the view, the touch, the sound, it’s a nice place to be. I become very aware of the moment when I sit in the Gesamthof. Time passes differently for all the inhabitants and visitors, and some of us spend a lifetime in this garden (most of the pigeons do) while for me it is very temporary. I will miss the Gesamthof when the new owners arrive in the monastery. But it doesn’t make it less worth it, on a larger scale gardening means ongoing change, and we can enjoy every moment of it. Never is a garden a fixed thing, it is never finished and there is no ‘end’, it just moves into different places.

Stills from Gesamthof: A Lesbian Garden, Annie Reijniers and Eline De Clercq, 2022.

Wild Bread

Il pane selvaggio (Wild Bread, 1980) is an essay by Italian philologist, historian and anthropologist Piero Camporesi about the experience of hunger in Europe in the modern age. Hunger in the Global North may appear to be a distant issue, but access to adequate, healthy and affordable food is still affected by profound inequalities both across the world and within single communities.

The “wild bread” to which the title refers describes the bread of the poor, who, to cope with grain shortages in times of famine, began to grind flour from roots, seeds, mushrooms—anything that could fill their stomachs and could be gathered freely on the limited non-private land available. The end product was stale, toxic and non-nutritious bread, which often also caused hallucinatory states.

The educated, rich and powerful men who reported the history of famines had the option of neglecting the experience of the most fragile people. Camporesi has therefore traced the accounts of those who could never aspire to a piece of white bread on their table in folk literature, as in the 16th-century song Lamento de un poveretto huomo sopra la carestia (Lament of a Poor Man Over Famine).

A bad thing is famine

that causes man to be always in need,

fasting against his will,

Lord God, send it away…

I sold the bedsheets,

I pawned the shirts

such that now my uniform

is that of a rag-pedlar,

to my suffering and greater distress

only a piece of sackcloth

covers this flesh of mine.

And even more it pains my heart

to see my child

say to me often, from hour to hour,

‘daddy, a little bit of bread’:

it seems that my soul leaps out

at not being able to help

the little one, oh terrible fate!

A bad thing is famine.

If I leave my house

and I ask a penny for God

all say ‘get some work’,

‘get some work’; oh proud destiny!

I don’t find any, despite all efforts

so I stay with head bent low,

oh fortune, cruel and evil

A bad thing is famine.

I have no more covers in the house

the pots I have sold

and I have sold the pans;

I am clean through and through…

Often my bread is made from

the stems of plants,

In the earth I make holes

for diverse and strange roots

and with that we grease our snouts:

and if there were enough for every tomorrow

it wouldn’t be so bad

A bad thing is famine.

Image: Luca Trevisani, Ai piedi del pane, 2022.

Oplà. Performing Activities, curated by Xing, Arte Fiera, Bologna.

A Sub-Optimal World

Olivier Hamant is a transdisciplinary biologist and researcher at the National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and the Environment (INRAE) in Lyon, and is engaged in socio-ecological education projects at the Michel Serres institute.

His book “La Troisième Voie du Vivant” envisions a “sub-optimal” future to survive the environmental crisis: in this interview, he promotes the values of slowness, inefficiency and robustness, and invites us to embrace a certain degree of chaos.

Authors and philosophers have always been inspired by the observation of nature to speculate about reality and society, but often with an instrumental approach. You too are inspired by nature, but from your point of view as a biologist, you come to some conclusions that challenge our prejudices on how nature works. How did your questioning begin?

During my PhD I worked on plant molecular biology, looking at genetic control and information. It was a clear example of an industrial framework transposed to biology: we used organigrams, we drew cascades of genes, we discussed “lines of defence,” “metabolic channelling” … Such semantics implied that life is like a machine. When I finished my PhD, I decided to try out a more integrated and interdisciplinary approach to get a more systemic view of biology. This confirmed that what I thought I knew was wrong: I’d been polluted by the concept of living beings as machines, and that’s where I started to deviate.

The book is, in fact, a real lesson in “unlearning,” as you overturn some contemporary concepts that may seem positive but ultimately aren’t, such as “optimisation.”

Optimisation is the archetype of reductionism: to optimise, you first need to reduce a given problem in order to solve it. When we solve small problems, we usually create other issues elsewhere. Take the Suez Canal for example: that’s a form of optimisation, of sea transport here, that makes us very vulnerable. A single boat gets stuck across the canal, and that’s it, you can’t send anything between Asia and Europe.

What about “efficiency”?

Photosynthesis is probably the most important metabolic process on Earth: it has existed for 3.8 billion years, and it’s the root of all biomass and civilisation. The “performance” of photosynthesis is usually less than 1%: plants waste more than 99% of solar energy. They’re really, really inefficient. Plants are green because they don’t absorb all the light; they absorb the red and blue sections of the light spectrum (the edge of the spectrum) and reflect the green part. Why do they waste so much energy? It’s now recognised that this is a response to light fluctuation. Light isn’t stable and capturing the red and blue sections allows plants to face such fluctuations. Plants manage variability before efficiency. They build robustness against performance.

Today, we see that the world is unstable, and it will become more so in the future: we shouldn’t be focusing on efficiency but on robustness. When we look for inspiration from biology, we often focus on circularity and cooperation. It’s a good start, but if we overlook robustness, it won’t work. For instance, if we come up with a form of efficient circularity, we won’t have enough wiggle room for extreme events, and we’ll exhaust the available resources anyway. If we make cooperation efficient, the win-win result will be counterproductive, and some will be left behind. Thus, robustness is the most important principle because it makes circularity and cooperation operational.

The most substantial criticism in your book concerns performance, drawing a parallel between violence against the environment and burnout.

Performance generates burnout—it’s a typical effect. Burnout applies to a person or an ecosystem. The path towards burnout is sufficient to condemn “efficiency at all costs,” but performance is also counterproductive in many other ways. A typical example is sports competitions: you want to be number one, you’ll do anything, including doping or cheating. That has nothing to do with sport and it’s detrimental to your health and career.

You also take concepts we interpret negatively and explain how they are actually positive, such as slowness or hesitation…

Slowness and hesitation are the keys to competence, as might be illustrated by stem cells. Biologists have focused on these cells for a long time because they’re extraordinary: they can renew all kinds of tissues. For a long time, we thought this was all controlled by a tidy organigram. It turns out that one of the key elements is that they’re slow: they hesitate all the time, and because they hesitate, they can do anything. Delays give some breathing space. I would actually go one step further: slowness is an essential lever for transformation. To change, you first need to stop. It’s like being in a car at a crossroads; if you want to change direction, you need to stop, indicate and turn. If you don’t stop, you won’t change.

Change is the keyword here. Hard science, numbers and prediction systems often lack the ability to consider contingencies or change, giving us the illusion that we have some form of control over reality.

Thankfully, we’ve made progress and now we use numbers to understand the unpredictability of the world (instead of using numbers to control it). For instance, in the lab, we’re working on the reproducibility of the shapes of organs. In a tulip field, all flowers look alike. You could think of an IKEA-like process: building things in the same way also makes them replicable. But this isn’t the case for living systems: when a flower emerges, some cells divide, others die, molecules come and go… Basically, it’s a mess. In the end, the miracle is that you get a flower with the same shape, colour and size as the neighbouring one. We showed that the flower uses and even promotes all kinds of erratic behaviours, precisely because they provide valuable information, to reach that reproducible shape. Once again, they build robustness against performance.

So, a certain degree of chaos should be embraced?

Sociologist Gilles Armani once told me a story about how to deal with impetuous rivers. The Rhône has all these swirls: if you don’t know how to swim through them, you might get trapped and drown. When people were used to living with rivers, if caught in the water flow, they wouldn’t fight it: they’d take in some air, let themselves be taken down by the swirl and the river would then let them out somewhere else, until they reached the shore. In a fluctuating world, the aim is no longer reaching one’s destination as quickly as possible, but rather viability, something which should be based not against, but on turbulence.

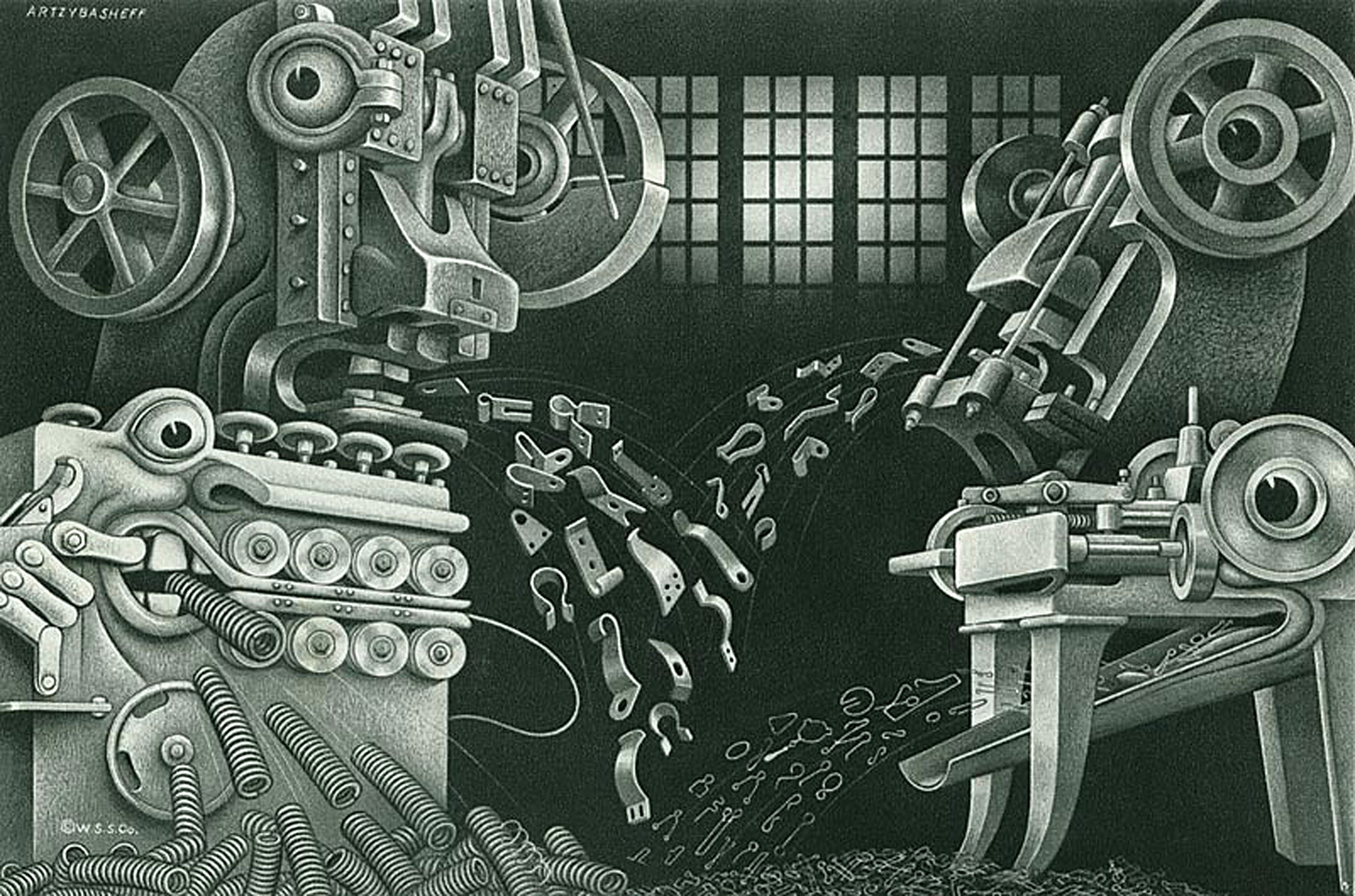

Image: Boris Artzybasheff.

Learning from mould

Reading

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Learning from mould